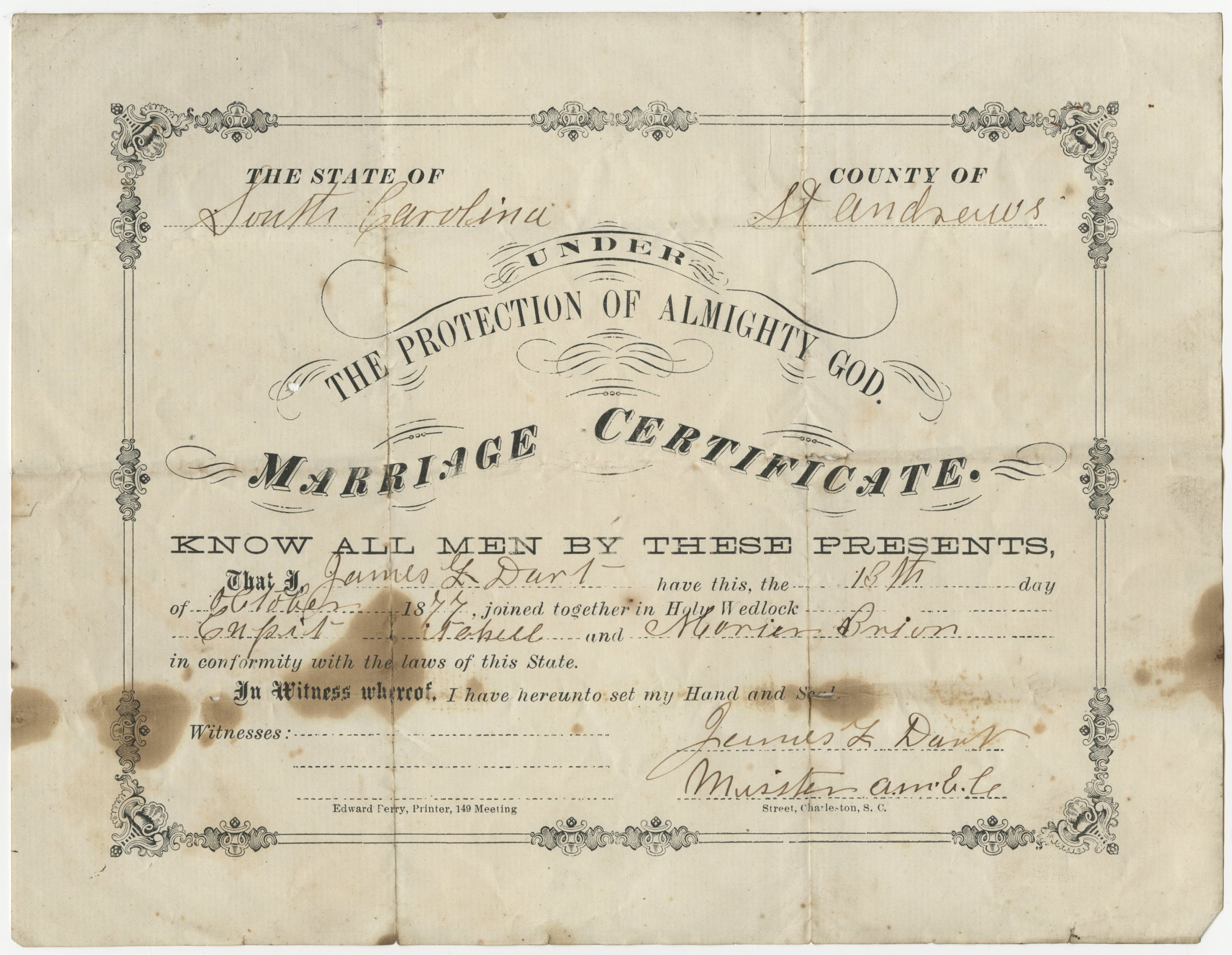

A marriage certificate for a wedding performed by Rev. James L. Dart, a minister affiliated with the African American Methodist Church, between Cupid Mitchell and Marion Brion represents small gains in freedoms during the Reconstruction era. “Enslaved persons had no legal rights to marry one another. Subsequently, families had no legal protections from abuses and caprices of enslavers and enslaved couples, mothers, fathers, and children were frequently torn apart. After emancipation, newly freed persons embarked on paths to find loved ones and to use the institution of marriage to assert some measure of legal control over their own fates. According to one scholar,

freed people hoped that legal, formalized marriages would allow them a respected social identity and choice: in their marital partners; in where the couple and their children would reside after marriage; and how they would structure their households. They wanted to participate in a ritual that legally recognized their unions. Hundreds of thousands of couples who had been married while enslaved, or wanted to marry after slavery ended, did not hesitate to participate in legally binding nuptials before the public, Black and White. These rituals pronounced to their families, communities, and the larger world that they now had a right to claim marital relations, control over the intimate aspects of their bodies and domestic households, and to bear, take care of, socialize, and maintain their children. Legalized marital relations, they insisted, drew a line between slavery and freedom.*

*Brenda Stevenson, “”Us Never Had No Big Funerals or Weddin’s on de Place”: Ritualizing Black Marriage in the Wake of Freedom,” in Beyond Freedom: Disrupting the History of Emancipation, ed. David W. Blight and Jim Downs (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017), 34.

Marriage Certificate, courtesy of the South Carolina Historical Society